Like a lot of my friends and contemporaries, the death of Neil Peart, the drummer and lyricist of the band Rush, hit me hard.

When I decided I wanted an electric guitar, my parents rightly decided that if it wasn’t to be a faddish thing that I lost interest in after a couple of days, I should save up the money to buy it myself. I did so throughout my 12th year on this planet, cutting a shitload of grass before I could walk into a shop where I bought four things:

- A very strange “Memphis” guitar with a single humbucker pickup, a 24 fret neck and a body shaped like the bastard son of a tele, an SG and a minecraft guitar

- A Crate amp from when they made them out of actual crates

- A cable

- A book – How To Play Rush’s ‘2112’ and Other Songs

A few years later, when I joined my first band, I asked if we could maybe play some Rush tunes at our first gig. Our drummer, named Cake, gave the definitive answer: “Are you crazy? Fuck no. Nobody can play Neil Peart’s shit.” It’s typical of my Quixotic life as a rocker that I started out wanting to play Rush, failed almost immediately, and never really got to, other than once or twice.

Rush were a huge force in the musical world of my youth. They’re often referred to as a “progressive rock” band, but they were very much a mainstream act. In the Great Lakes region where I grew up, and in Canada, they might have been the biggest band of their generation. From a radio-play point of view, they were anything but esoteric. And they were a huge presence on MTV in the pre-Michael Jackson years when that network was worthy of its original name: “Music Television.”

And, yet, Rush were unabashedly musically ambitious. They showed that complex musical compositions based on highly intellectual lyrics, full of changes of meter and tempo, with extended flights of instrumental virtuosity, could achieve vast mainstream popularity. Likewise, that a catalogue of songs with nary a traditional love song among them could be embraced by millions of record buyers and dominate FM radio for almost a decade.

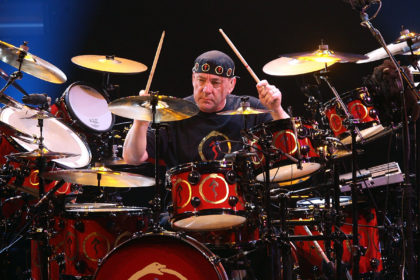

There have been countless tributes to Peart online already. Almost all of them mention his virtuosity as a drummer. That Peart was a virtuoso of the highest order has been recognised for years. One of the reasons that Rush’s popularity as a live act never waned in spite of the more-or-less consistent loathing and disdain of rock ‘critics’ is that all three of them were such fantastic players that one went to their concerts just to see them play.

And it’s important to remember that when Peart exploded onto the scene in the 70’s, his kind of virtuosity was something that rock music hadn’t seen before. British prog rock bands of a slightly older generation had certainly been incorporating complex time signatures for some time, but Peart was able to play in any time signature with a kind of rigour, power and clarity that made less ambitious listeners forget that the music wasn’t in 4/4. Nobody in his generation had more technique behind the kit that Peart did; there was speed, power, fluency, groove and flair. But there was also security. He spoke 13/8 like John Bonham spoke 4/4.

These days, every young drummer coming out of school is expected to be able to play something like YYZ without too much struggle. One generation’s unattainable virtuosity is the next generation’s baseline of competence. Peart set a new standard for technique, but technique is fairly easily copied and learned. Peart’s more enduring contribution as a drummer not that he could play all those great parts, but that he came up with them in the first place. Playing the drums like Peart is not easy, but many can now do it. Coming up with drum parts like Peart’s? I don’t know anybody who can do that.

One of the things that makes me the most sad about Peart’s death is that it seems to put another, possibly final, nail in the coffin of the idea of the rock band as a creative collective, an idea that was as beautiful as it was new when it emerged in the 60’s and 70’s.

A certain subset of ‘musicologists’ have lately taken to championing the completely spurious idea of historical “collaborative creativity.” In this view, we look at great composers of the past not as creative geniuses but as part of teams who ought to share the credit for their work. In this view, the Beethoven string quartets are not just Beethoven’s achievement, but that of, I don’t know, his neighbours? His cook? Sure, Wagner wrote the words, the music and the stage instructions for his operas, but shouldn’t he share the writing credit with…. Well, it’s amazing that people who come up with this stuff can pay their rent. But it’s very zeitgeisty right now in a Trumpian, “up is down if I say it loudly enough” way that is particularly popular now in progressive-leaning academia and right-wing politics, who have more in common than either party wants to admit.

Such a re-interpretation of the past is not only completely without factual basis, it greatly short-changes the innovation of more recent actual creative collectives like Rush.

Rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t originally a particularly collaborative form. In the early years, it was dominated by star singers, not bands. The major artists of the 50’s are mostly individuals, not groups – Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Chubby Checker, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly. Most white singers sang (a better word might be “stole,” a la Pat Boone) other people’s tunes. Even most ‘bands’ (The Coasters, The Drifters, etc) were defined as a group of singers, backed-up by a faceless and anonymous team of studio musicians.

But with the arrival of the Beatles and the Stones, things started to change, and by the 70’s, groups like Rush, Queen and Led Zeppelin represented something of a high-water mark of the rock band as a tightly-knit, almost completely self-contained creative entity, one that survived into the 1990’s. At its best, this ethos meant that every aspect of the music came from the group, including composition, arrangement, production, design, playing and singing.

I can’t think of any precedent for this approach in Western music. We can see in the cases of Haydn, Bach and Ellington (among others) examples of composers and arrangers building hand-picked ensembles in which the musical qualities of the members helped stimulate and direct the creativity of the composers. Jazz has always been considered a more democratic art form, and, yes, when a soloist is improvising, their choices are their own. But jazz is also pretty hierarchical. Whether in the age of big bands or in the era of smaller groups which followed the bebop revolution, the leader sets the tone, picks the tunes and creates the vision. Most importantly, they hire the other cats. In Miles Davis’s case during the 1960’s, that might have meant that Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock were actually writing most of the material, but that Miles was still setting the direction of the band.

Not all great rock bands were collaborative in this way. The Who had four huge personalities in the original group, but only one dominant composer, Pete Townshend. Townshend is himself a good singer, so why did he need Daltrey, Moon and Entwistle? Listen to a Pete Townshend solo album, and you’ll see why, but there’s no denying that The Who were primarily (not exclusively) a vehicle for Townshend’s creativity. As The Police were for Sting’s. Or Dire Straits for Mark Knopfler’s.

But for the bands that committed themselves to a collaborative way of working, it was an approach to music that brought together writing and performing as part of a unified approach to creativity which defined the album as a new kind of Gesamkunstwerk.

Balancing the creative ambitions and needs of several musicians in one band was never easy. In much of their early career, the thing the members of Queen fought over the most was whose songs would end up on the next record. Song writing royalties were worth a lot, so there was a huge amount at stake in deciding which songs would get recorded and who would get credit. It’s now well known that the Lennon–McCartney partnership didn’t really last through the Beatles run, which was just ten years. Over the years, Paul and John became more and more independent in their work, but keeping the shared writing credit meant that there was less incentive to fight over royalties. Queen eventually adopted the solution of shared authorship for all their songs starting with “One Vision.” (Although Brian and Freddie were the most prolific composers in the band, both John Deacon and Roger Taylor made major contributions to the Queen catalogue, certainly more than Ringo, and arguably more than George, did in the Beatles). The case of Led Zeppelin, on the other hand was interesting. In some ways, one of the most tight-knit of bands, each album seemed to mark a different balance of creative contribution, and they always borrowed quite a lot from earlier blues and rockabilly acts, too. When they lost Bonham, that was the end (as it was for Queen when Freddie died), where other bands reinvented themselves with varying levels of success through changes of personnel. Pink Floyd started as Sid Barrett’s vehicle, became more collaborative for a time with David Gilmour, Roger Waters and Rick Wright sharing writing and production, but ended up as almost a Roger Waters solo vehicle by the time of The Wall and the Final Cut, with Wright and Gilmour more in the role of star sidemen like Anton Kraft or Johnny Hodges. Eventually, Waters was out and Gilmour was left in control but didn’t have a gift for lyrics of his own.

In Rush, it was Peart who wrote the lyrics, Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson who wrote the music, and together they all worked out their own parts, and the shape and arrangement of each song. Peart said that Rush was not a democracy, but something more: “You can’t have a democracy in a three-piece band, that would just be two against one. Everything for us had to be by consensus.”

Once Peart joined the band in 1974, Rush was the same three guys for more than forty years. In that time, the band went through many changes of direction, but no changes of membership. This included changes in the subject matter of Peart’s lyrics. It included changes in the kinds of compositions they were working on, moving from long, complex works towards shorter songs, and changes in instrumentation and production techniques. Through it all, they seemed to navigate all these changes in a way that strengthened their sense of teamwork, and their 19th and final album still shows them at their best. That they navigated all of these changes yet stayed friends tells one they must be exceptional people, not just exceptional musicians.

When I was first falling in love with rock in the late 1970’s, Rush seemed normal. Amazing, but normal. Their music was everywhere, and their way of working seemed like the way things were to be done. They embodied what a rock band could and should be. And they found a huge audience for their unique music.

My limited forays into the world of bands quickly showed me that managing the complex interpersonal and artistic dynamics of a band is incredibly difficult, and only gets more challenging as the stakes get higher. It’s almost the same in chamber music. In a string quartet or trio, one can argue about everything from bowings and intonation, to tempi, style, balance, programming and stage presence. There are issues to do with travel time, issues to do with who gets the gigs, who speaks for the group. But at least, most of the time, chamber music ensembles are not playing their own music. Imagine a string quartet arguing not about whether or how to play Beethoven or Brahms, but arguing over whether to play the cellist’s new piece or the 2nd violinist’s, knowing the decision could have huge financial implications for both parties. Or arguing over the fact that the violist has announced that she’s now switching to synthesizers for the new album?

So maybe it was naïve to think that creative collaboration as embodied in a handful of rock bands was ever the way of the future. If so, it means we ought to be all the more admiring of the achievement of guys like Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neal Peart, who made this seemingly impossible balancing act look easy.

And while the death of Neil Peart is a gut punch for a generation of us who remember putting the boombox in the window and blasting out all of Moving Pictures for the benefit of our neighbours (sorry about that!), maybe it’s a timely reminder that rock can be a more aspirational form than what remains of it now is. Fuck America’s Got Talent, the X-Factor, boy bands and girl bands. Fuck all those fucking tribute bands cannibalising the rotting corpses of great bands of the past. Fuck the lip-sync-ers and the auto-tuners. Fuck the thieving samplers, and the front-men and front-women who never learned to sing. Why spend your life singing other people’s songs when you can write your own? And if you haven’t got the writing spark, why not be another Daltrey, Hodges or Gilmour? Help your Knopfler, Ellington, Waters or Townshend to bring their vision to life.

The day before Peart died, I read a sad interview with 70’s-era teen idol Leif Garrett. He spoke of spending his years of peak celebrity feeling like a fraud – it was his face selling other people’s songs, playing and even singing. It’s not a happy story – putting his face on corporate music nearly killed Garrett, who struggled with drugs and depression. But Garrett was the future. He is today’s normal. We don’t have to bother with ghost singers anymore, we have autotune. We don’t even need session players – we can just sample other people’s records. And now, with Peart gone, the idea of a band of brothers and sisters doing it all themselves disappears even further into life’s rear-view mirror.

Now is the moment when we need more young players to find two or three or four like-minded friends and lock themselves away in a basement and write their own songs, play their own instruments, make their own arrangements, tell their own stories, create their own paths. It won’t be easy. Most of you will end up throwing chairs at each other during a band meeting, or watching Spinal Tap in the horrifying knowledge that it is more documentary than comedy. But you’ll make the world a far better place for trying.

In one of his last interviews, Peart was asked what the secret was to Rush’s incredible run:

“Always doing what we believe in and believing in what we do, writing songs that we still like 30 years on and can still play with conviction.”

A great lyricist once wrote “Hope I die before I get old.”

Maybe the wiser lyric would have been: “hope I don’t outlive wanting to play this song I wrote, or wanting to play it with the friends I wrote it with.” I know at least one lyricist who could have found the right way to express the sentiment.